"It doesn’t matter. Just keep telling the story."

On Asteroid City and the impossibility/necessity of art

We can forgive a man for making a useful thing as long as he does not admire it. The only excuse for making a useless thing is that one admires it intensely.

All art is quite useless

- Oscar Wilde, in the preface to The Picture of Dorian Gray

Spoilers ahead for Asteroid City

If the TikTok trend of portraying one’s life or workplace as a Wes Anderson film is anything to go by, everyone thinks they know what comprises the American auteur’s style. With the trend at its height in the year before the release of Asteroid City in June, this quasi familiarity almost becomes another framing device for a film already containing several framing devices. Asteroid City is a film about a television broadcast about the production of a fictitious play (also called “Asteroid City”) about a small Western town’s junior science competition derailed by unexpected happenings.

Asteroid City’s colour palette is heightened, its scenarios absurd, its dialogue deadpan, its models painstakingly and lovingly constructed, and the blocking of camera and people impeccable. The camp that believes Anderson is style over substance will not have their minds changed by this film, but seeing a director work so assuredly, to tight choreography of actors and cameras, is a relief in an age of directors not knowing what they want.

By the film’s end, Asteroid City perfectly refutes two seemingly contradictory beliefs: that art must serve a utilitarian purpose, and that art is meaningless.

Art must be utilitarian

The first weekend Asteroid City came out (well, every week since November, in peaks and troughs), a scroll through Twitter has revealed new ways in which Art Council England’s drastic cuts to arts funding are hitting theatre and opera hard. Making matters worse, these decisions seem applied with little logic, demoralising an entire sector (that more than pulls its weight by bringing money into the UK’s economy). How would “Asteroid City”’s director Schubert Green fare today, instead of in the fictionalised but recognisable landscape of postwar American theatrical innovation and social awareness, and the corresponding public support?

In an interview published that same weekend, longtime theatre critic Michael Billington spoke about his (anecdotal) observation of change in the arts over the past four decades:

A lot of plays and films are getting increasingly about other plays and films. Are the arts getting dangerously incestuous? Are we at this moment more fascinated by plays about plays, films about films, musicals about musicals? Is it because of a lack of creative dynamism within the culture?

Perhaps this trend is an attempt to prove the effort and purpose that goes into these creations and justify their existence in a (hostile, difficult, capitalist, profit-driven) reality. Such works can be exhausting and navel-gazing if utilitarian to their own ends, but Anderson’s is not this. His recreation of the television studio and stage highlight the craft, doubts, and collective leap of faith that brings a new work to life. The process of creation itself is sometimes (often? always?) more important than the whys and wherefores. Asteroid City is a forceful refutation of usefulness and didacticism; it is proof not of art for art’s sake but the small acts of humanity comprising and revealed by ‘useless’ fiction.

Art is meaningless

“Asteroid City” (the play) is fake, made up for an educational television broadcast about how such a piece of theatre might come together from writing to rehearsals to catching a fed-up actress mid-flight to the performance itself. In this instructional format, it grows from the utilitarian art that is easy to explain to funders. Thus, at the end of the day, all motivations within both plots could be called meaningless. But the effect is far from it. In the hands of Anderson and his extensive, well-matched, star-studded cast, the journeys taken by a doubly fictional group of players has tangible repercussions for all.

First, the collective creative journey. “Asteroid City” comes alive as it is written and workshopped by Conrad Earp (Edward Norton) with the help of Strasberg-esque acting teacher Saltzburg Keitel (Willem Dafoe). Conrad has shades of Arthur Miller and shades of Lynn Riggs with a hefty dose of Cold War retrofuturism. Conrad struggles to connect character, action, and motivation throughout the play’s genesis; these are often revealed as the bolder, less obvious choices in the play-within-the-film. Workshopping with actor Jones Hall (Jason Schwartzman) and Saltzburg Keitel’s studio class joins the dots and brings characters off the page and into living, breathing dimensions. Nothing seen in these black and white 4:3 rehearsal scenes makes its way into the technicolour Cinemascope “play”, emphasising the importance of this workshopping and creative exploration. It is not all about the end product.

Second, the individual journey. In a mirror of rehearsal room experimentation, war photographer and recent widower Augie Steenbeck (played by Jones Hall, played by Jason Schwartzman) and actress Midge Campbell (played by Mercedes Ford, played by Scarlett Johannson) both work through their art together when stuck in Asteroid City in the play-within-a film. She models for him, he runs scenes for her; Augie’s photographs are physical, visual reminders of the experiences, Midge’s films live entirely offscreen. Augie is grieving, with four children in various stages of maturity, acceptance, and understanding of their mother’s passing; Midge wears greasepaint black eyes as a metaphor for her character’s journey and shows more than a passing attraction to the suicide her character gets to act out. These artistic practices are key to Augie’s and Midge’s own self-perception and awareness - even when (more later) they don’t make sense to Jones/Mercedes.

In a brilliant bit of scene-setting, Asteroid City is in the middle of the desert and regularly shaken by atomic bomb tests. Global annihilation is just around the corner. These little meaningless moments of creation and connection - photography, rehearsals, groundbreaking scientific innovations, a schoolboy’s song with some backup cowboys, and endless dares - are all this mismatched crew can control. The impact these actions have, however, touches every character, and by extension the audience. The art means something.

Art is useless, and meaningful

Asteroid City hinges around this artistic process and the connections made with people in the face of events that cannot be easily or rationally explained (be they strange visitors, or a sudden offscreen car crash). The film does not argue that making art is of utmost importance or the ultimate aim in life, but - in a world where art feels increasingly restricted by budgets, brands, and expectations - Anderson’s film understands that our connections to ourselves and others are made richer through creativity.

As the play-within-a-film drama reaches a frenzied climax, the culminating moments of Asteroid City itself takes a step back and around, sidestepping the chaos on stage/screen to instead explore the process of creation. In the scripted chaos, Jones - who provided Conrad with the explanation for Augie burning his hand on the stove - leaves the stage and breaks out of Augie to confess to Schubert that “his own personal heart” breaks night after night; Jones and Augie have both recently lost their partners. Must he continue to do it, without answer or understanding? The director reassures him, telling him that it doesn’t matter: “Just keep telling the story. You’re doing him right.”

Jones finds a strange moment of peace and closure with the actress (Margot Robbie) who was initially cast to play Augie’s deceased wife in a dream sequence, and then - missing his cue - runs back to finish the show. Here, meaning and theme are suspended and secondary, left up to Jones/Augie, Schubert, Mercedes/Midge, and the entire company to push ahead with the action and see the strange events to their end. Ultimately, to paraphrase Schubert, we just have to tell the story. We’re doing it right.

***

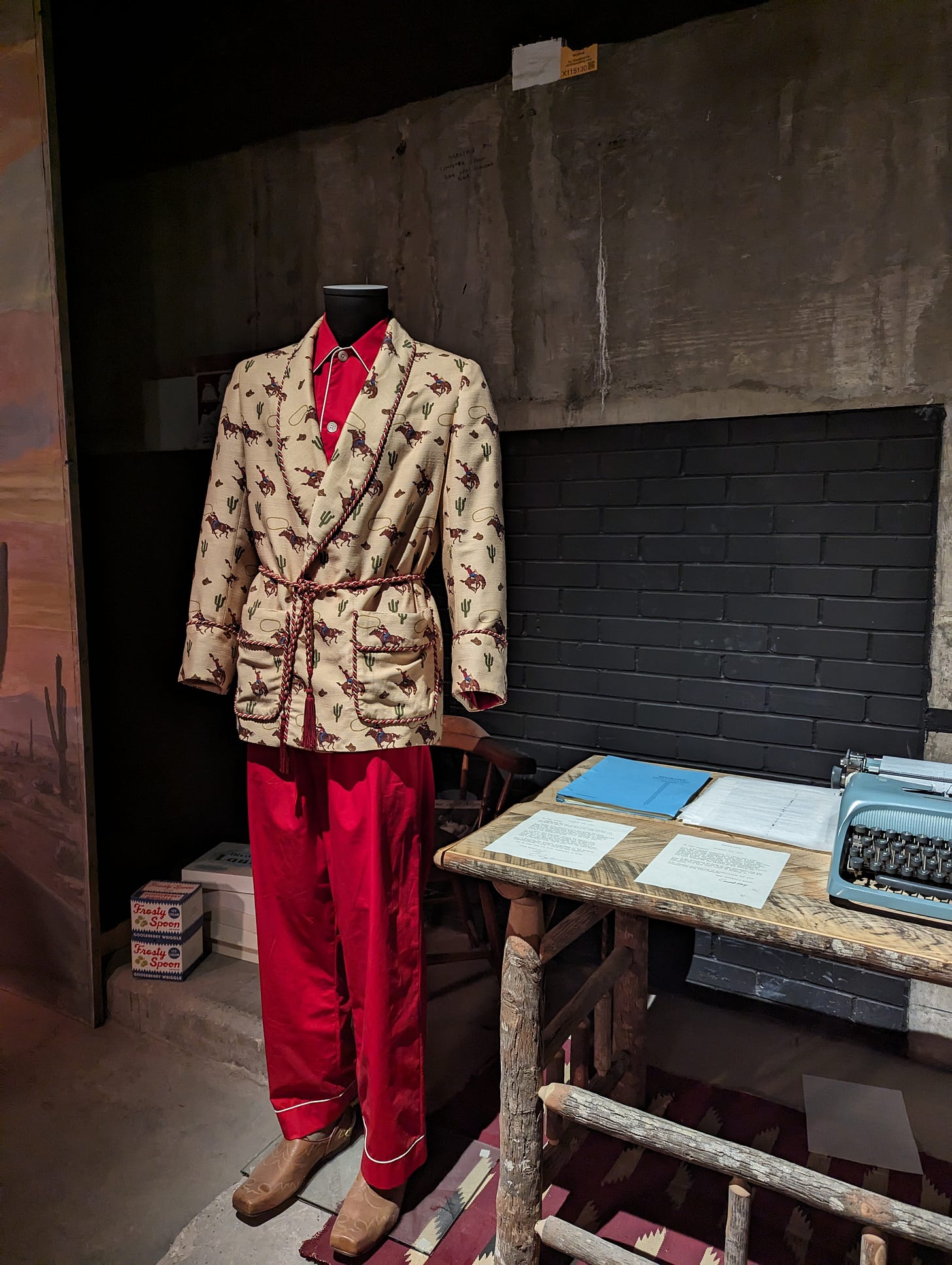

I wrote about Tár (in January) in a mad frenzy after seeing the film; this one came much harder, after two viewings and one visit to the exhibition at 180 Studios. Summer life is a bit busier than the depths of winter, but it is also harder to think about art’s purpose and value when it seems to be under relentless assault.

Two weeks ago, I took a half-week holiday to go down to London and its surroundings and see lots and lots of opera (and the Asteroid City exhibition). It felt like a useless holiday - I was not going anywhere exciting or new, except into fictional worlds full of good music. Before setting out, I was wondering if I was using my annual leave and budget appropriately.

It was, quite possibly, the best half-week of my life - a complete escape from reality in favour of sweeping romantic dramas (Werther and Tristan und Isolde at Grange Park Opera, both perfect fits for the Theatre in the Wood’s intimate space) and sweeping historical epics with private heartbreaks (Don Carlo at the Royal Opera House). I’m unendingly lucky to have had this opportunity to see experts in their field - John Doyle’s emotionally astute direction, Charles Edwards’ scenic marvels, Lise Davidsen’s eardrum-vibrating pianissimo (an oxymoron? Not for her!) - at the top of their game, and be moved by their stories and craft. The best art is so useless, but its place in life is irrefutable and irreplaceable.

***

What I’m reading

Booth by Karen Joy Fowler: while I’m only halfway, this is skillful historical fiction in that, as the author weaves through the several perspective children in the Booth family, she knows that most of us will already know how (one facet of) the story will end. This does not manifest in continued references to Big Events but also in small observations on drink, relationships, and seemingly minor forks in the road - author and reader look forward and back on lives as the characters cannot see what course they have set for themselves.

What I’m watching

The best thing that can be said about Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny is that Harrison Ford (when not uncannily de-aged) seems to be having a nice time.

What I recommend

A brilliant piece by Fran Hoepfner on Asteroid City, more on the story within the story.

I’m running a marathon in September! I’m excited, it’s getting daunting. Writing this piece today has taken the place of a training run because after yesterday’s 14 miles I’m shattered (I’ll be back at it tomorrow). My marathon place is in support of one of the Berlin Marathon’s UK partner charities, the National Literacy Trust, and so I’m aiming to raise £1200 in support of their fantastic programmes across ages and demographics (I find their work in prisons especially inspiring). If you have some spare change and want to donate, my JustGiving page is here.

Support the WGA and SAG strikes!!! AI is stupid and corporate greed worse.