The Tonys (Broadway Christmas) happened on Sunday night, and the online musicals community collectively celebrated by watching Audra McDonald’s rendition of “Rose’s Turn” on repeat. But as much as I’m captivated by Broadway’s current productions and winners, be they the two I saw live (Death Becomes Her and Oh, Mary!) or ones I want to seek out (all, but mainly Maybe Happy Ending and Dead Outlaw), my current musical theatre obsession is older – eight decades older.

My annual Spotify Wrapped tends to be a foregone conclusion by April. This is the point of the year when, mornings and moods growing lighter, I’ve latched onto an album with a ferocity bordering on addiction. This lasts throughout the long summer days and into the waning autumn, and even if I’ve started rotating in other albums by then, Spotify stops counting music after 31 October. The first Wednesday of December, there might be some fun graphics and silly stats to share, but surprises? Absolutely not.

For the past three years, these albums have all been musicals and my “most listened” artist is usually the composer, arranger, or star (Spotify has no good way of categorising musical theatre, opera, or symphonic music – its second biggest flaw after not paying artists enough). In 2022 it was Cyrano, Joe Wright’s heartbreaking film adaptation of the Dessners’ pre-pandemic stage musical starring (from the stage) Peter Dinklage and Haley Bennett; Bryce Dessner ended up as my top artist. In 2023 it was Oklahoma! (the sexy and spicy version as reworked by director Daniel Fish and re-orchestrated by Daniel Kluger); star Damon Daunno was my top artist. In 2024 it was, big surprise, Assassins (the 2004 Broadway recording that has never been better, and the only recent musical album obsession with composer Stephen Sondheim listed as the primary artist).1

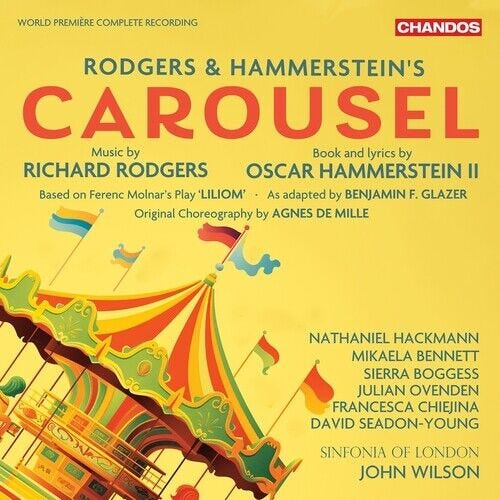

This year, it’s Carousel - Rodgers and Hammerstein’s 1945 musical loosely adapted from Ferenc Molnár’s 1909 play Liliom. While I’d heard a couple recordings in the past, in its eightieth year it’s broken something in my brain that can only be alleviated by immediately starting the recording over and getting back on the ride. The obsession got so bad a couple months ago – the week of Carousel’s exact eightieth anniversary on 19 April – that I ended up forcing myself to take a break from my favourite recording (Sinfonia of London conducted by John Wilson, 2024) and listening instead to every other professional recording I could find on Spotify: the 1945 Original Broadway Cast recording, the 1956 film recording, the 1993 London production, and the 2018 Broadway revival. The Sinfonia of London recording wins (more on this below), but the itch was not fixed – it only intensified, time and again.

Molnár was courted by the likes of Giacomo Puccini and Kurt Weill for the rights to adapt Liliom for the operatic and musical stages, but he turned them all down; he didn’t want his work to get a sentimental operatic treatment. He was, however, convinced Rodgers and Hammerstein were the right adaptors after seeing Oklahoma! on Broadway, even approving the new final scene the pair added to make the story just a bit more palatable and uplifting for Broadway audiences.

In hindsight, Molnár made an entirely correct choice. No one has had a better first run of musicals than Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II. Oklahoma! (1943), Carousel (1945), and South Pacific (1949) are all stone-cold bangers. In each, the duo deconstruct an American ideal and find the darkness underlying these realities – granted, all end happily to a certain degree or another, but a reading of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s work as sunny, easy, and/or old fashioned is frankly incorrect (their later musicals did soften into sentimentality, especially The Sound of Music, but the bad guys in that one are literally the Nazis so it’s impossible to call it entirely escapist). Oklahoma!, usually the sunniest of them all, examines an insular community on the verge of societal change and, after a shockingly violent wedding, takes a brief detour for a very informal murder trial. South Pacific ends its first act with the American heroine realising she’s too racist to date a man with mixed-race children (thankfully, she grows as a person by the end of Act Two and remains the “heroine”). And Carousel, in the middle, is about ordinary people and ordinary problems: poverty, unemployment, domestic abuse, crime, suicide, and a quest for redemption beyond the grave. As Sondheim said, “Oklahoma was about a picnic. Carousel was about life and death.”

Carousel centres on two romances: that of carnival barker Billy Bigelow and mill worker Julie Jordan, and that of Julie’s friend and coworker Carrie with the ambitious fisherman Enoch Snow. Billy and Julie are married by the second scene, after swearing that they weren’t the marrying kind – and that any action they take would only be “if” they loved the other (no one writes a not-in-love love song like R&H – “People Will Say We’re in Love” from Oklahoma! and “Some Enchanted Evening” from South Pacific also capture the same wouldn’t-it-be-funny-if-this-happened deflection of Carousel’s “If I Loved You”). But in staying out all night to tell each other what they’d do, if they were in love (but they aren’t), Billy and Julie are both fired by their employers, starting married life in a precarious position. It’s the harsh way of the world, and as Billy sings:

There’s a hell of a lot of stars in the sky

And the sky so big the sea looks small

And two little people, you and I

We don’t count at all.

As Mr Snow and Carrie’s romance unfolds traditionally – an engagement, a post-engagement fight, then marriage and nine (!!!) children – Billy and Julie’s path is far more complex. Julie is soon pregnant, and Billy decides the best way to provide for his family, having found no luck getting a new job, is to join is ne’er-do-well friend Jigger in a robbery. When that goes very wrong, he kills himself (only when he’s dead does Julie tell him that she loved him). Still defiant in the face of a higher power’s judgement, he is given the chance 15 years later to go back down to Earth and do something good for the now-teenage daughter he never met – and maybe tell Julie, finally, that he loved her. Cue the tear-jerking finale set to “You’ll Never Walk Alone”.2

Carousel is like It’s A Wonderful Life if George Bailey was the world’s biggest asshole, because the story gets thornier from here. Billy hits Julie. It only happens once offstage, if the script is to be believed and everyone is telling the truth. But Billy and Julie are both unreliable narrators and – their own denials of love aside – prone to talking obliquely, if not outright lying, at various points of the show. And it boils down to each production’s interpretive choices whether Billy turns into a domestic abuser or merely (still unacceptably) a man who lashes out in stress; let’s not forget that, when granted one day on earth to try to make things right for his family, he hits his daughter when she refuses his gift of a star.

Most of the discussions of domestic abuse happen between songs and, if you’re just listening to most albums, you miss its explicit mention – the libretto has to fill it in – though the story’s darkness and complexity is captured in the surrounding music and lyrics’ emotions. The 2024 recording is the first “complete” recording capturing all music, and includes Julie’s extraordinarily problematic line that “it is possible for someone to hit you, hit you hard, and not hurt at all”. The possibility of unreliable narration aside, it’s ridiculously hard to square eighty years later,or 116 years after Liliom’s premiere in Hungary. The way the story’s intrinsic domestic violence is presented by directorial and performance choices change the reading of this deeply unhealthy relationship with each interpretation.

But I truly do not think Rodgers and Hammerstein (or Molnár) intended to glamorise or glorify this relationship. In the script, Julie is the only one who comes close to forgiving Billy – she just says she knows he hit her because he was unhappy. Everyone else – from Carrie to the Heavenly Friend and Starkeeper who takes Billy to his judgement – condemn him, or at the very least hold him to account. Louise, their daughter, carries the ruinous emotional reality of having a parent that she never knew and hears conflicting – mostly damning – stories of. Carousel gives us situations and characters who behave counterproductively, if not just plain terribly, and expects us to find a point of identification with them. Holding its richly realised world in my mind, it reveals new facets with each turn.3

Between this arresting complication and darkness, Rodgers and Hammerstein give Carousel’s characters words and music that soar, balances levity with grandeur, and never loses sight of their inherent if often squandered dignity. Before the iconic songs – “If I Loved You”, “Soliloquy” (more below), “What’s the Use of Wond’rin”, and “You’ll Never Walk Alone” – even begin, The Carousel Waltz is dramatically singular. As the musical’s overture, it is not a hodgepodge of other songs heard throughout the show. It is its own theme, recurring later only in orchestra-only sections of the musical. It falls down the scale only to leap back up in chords, the strings lighty dancing through the melody while the brass hints at a darkness – a danger under the frolicking. The Carousel Waltz is almost as much of a character as the people who appear in the story, acting as its own impartial force sweeping them along. In it are the tawdriness and petty thrills of a small town fairground; in it are also the hopes, desires, and aspirations that make each human life a universe in itself.

“Soliloquy”, an eight-minute number at the end of Act One where, is still rarely matched and never surpassed in the musical theatre canon. Sure, Billy’s dreams about and hopes for his unborn child are gendered in a way that kind of anchors the show to its 1870s setting and 1945 premiere, but the superficial datedness does not hide eight impeccably-crafted minutes of self-discovery. He buoyantly imagines a son who has all his best qualities and none of his worst ones, and then he realises his child might be a girl. “What would I with her? What could I do for her?”, he muses with budding terror before bursting with pride at a new, equally magical fantasy. And then, reality comes crashing in again, towards an elemental and timeless fear of inadequacy that drives him to do anything – anything – to ensure she has a better future than he did.

In Carousel, everyone has dreams, and some people achieve them – at least on the outside. Carrie gets her happily-ever-after with Mr Snow, though her snarky asides and sneaking into a raunchy Broadway revue reveal stealthy compromises in her picture-perfect world. Others, like Billy and Julie, fail at their dreams time and again, sometimes through the misfortunes of chance and sometimes through their own active self-sabotage and self-destruction. Billy loses his job because he refuses to ban Julie from the carousel, he makes himself an outcast through his violence and intractability, yet when he tries to turn things around he falls foul. The robbery Jigger convinces him to commit to get money for his growing family? Before they even set foot in the mill, the pair gamble on the earnings, and Billy loses – meaning he won’t see a penny from his crime. Then, in another twist of fate / dramatic irony, the money isn’t even there – Mr Bascombe the mill owner has transferred it all to the boat that night, and instead of cash the duo find him at the mill with a gun. So Billy takes his life, readier to face the judgement of an unknown higher power than jail time, all for naught. When finally given a chance to come back to earth to do one good thing for Louise – to bring her a star from the heavens – he cannot handle her rejection and hits her too, even after seeing that she’s been through “somethin’ like what happened to you when you was a kid”, as the Starkeeper says. His is a catalogue of personal failure, brought about by a rough life and those who want to keep the likes of Billy in their place, but exacerbated by his own wrong choices.

Yet, throughout Carousel, Rodgers and Hammerstein ensure that Billy and Julie hold the story’s heart. Despite Billy’s assertion that they don’t count at all, every choice they make holds the possibility of happiness or devastation, and each time through the score – each time I press play on the Carousel Waltz – makes me wonder if maybe this time they won’t make better choices. Perhaps they tell the other they love them while they’re both still breathing, or perhaps the best choice is that they do not end up together. Their lives, and the lives of everyone in their small fishing town, contain every facet of the human experience. Some may say “You’ll Never Walk Alone” is an on-the-nose refutation of Billy’s ethos, but the idea of moving ever forward “though your dreams be toss’d and blown” when seen against Billy’s and Julie’s own shattered dreams feels like a necessary truth of life, not a nice comforting lie.

When reviewing the 1994 Broadway revival (which starred Audra McDonald as Carrie in her first-ever Tony nominated performance), the New York Times called Rodger and Hammerstein’s choices “bold and risky” saying

…this is a luminescent musical shot through with pain and bewilderment, an uplifting musical in which the lives of most of the major characters are either miserable or misspent. The paradoxes and contradictions are precisely what keep "Carousel" alive and vital. The simpler-minded entertainments tend to die young.

I would agree.4

Carousel is a musical with achingly beautiful melodies about unimportant people on an unimportant stretch of coast who get second chances that are in many ways entirely unearned. Yet in the end, their mundane sufferings and triumphs are no less meaningful than the cosmic ones. Its conviction is jagged, difficult, problematic, and endlessly moving. If there’s hope for Billy Bigelow, there’s hope for all of us little people.

***

A subjective but also correct ranking of Carousel recordings:

2024 studio recording: leaves very little to be desired, possibly definitive. The cast is on heartrending top form and the full score conducted with a lush 35-piece orchestra.

1993 West End: dramatically impeccable, excellent music direction, but the roughest voices of the bunch

1956 film: absolutely unreal the colours Gordon MacRae can paint with his voice.

2018 Broadway: this is the first recording I heard and, despite an A-list cast and the best Carrie on record in the form of Lindsay Mendez, it really doesn’t cut it. “You’ll Never Walk Alone” is Disney-fied with its one-line-per-soloist and “Soliloquy” is taken way too fast (a minute faster than most other recordings!).

1945 Broadway: absolutely no offense to the original but the recording technology is very dated and it’s extremely truncated to fit an LP. But John Raitt’s final note of “Soliloquy” must be heard to be believed.

This was my first entry in a while, and somewhat an inadvertent follow-up to Great American Art. Someday,hopefully soon, I’ll actually see a production of Carousel and I’ll come back to revisit my takes here (if anyone involved in theatrical or orchestral planning is reading this, I’d pay truly stupid money to see a fully staged production with the full band). I hear the film version of Carousel doesn’t work as well because it relies so much on stage magic, and it was cut to ribbons for both run time and Hays Code reasons. If you’ve seen it, what did you think?

I’ll be back with another post with my usual reading/watching/listening section; in the meantime, here are a few pieces I cannot recommend enough.

Obviously I had to include Kate Wagner’s Ring Cycle masterpiece for VAN Magazine, a piece that holds its own with Shaw’s and Cooke’s works. If you love the Ring, it’s a must. If you’ve never heard of the Ring, this is the best place to start. If you only know Brünnhilde through Bugs Bunny, well, you know everything there is to know already (kidding, read it).

This is the best of literary and social criticism.

Back to the Tony Awards, this breakdown of Cole Escola’s awards ceremony outfit is a treat (they wore a necklace with Laura Keene on it! That’s demented! I’m in love!)

This is the only correct main artist when categorising operas, musicals, and symphonic works.

I’d love to see Carousel live in the UK at some point, as I’m guessing at least 50% of the audience won’t know the Liverpool FC song is from this show.

One of my biggest pet peeves in modern musicals is the tendency to sing narration – as much as I adore Natasha, Pierre and the Great Comet of 1812, it’s a culprit. Hammerstein, and Sondheim, never do this, and perhaps counterintuitively it’s easier for the world to take shape in my mind this way.

The NYT also profiled Michael Hayden, who played Billy in 1993 on the West End and 1994 on Broadway. I was struck by this testimony: “It might be a dark play, but it brings out the humanity in people," he says. "It opens up a deep well of feeling. There are nights when I come back to my dressing room and just cry because it goes so deep. It feels like I've scraped out a new part of myself that I didn't even know was there.” Ouch!